Structuring an Online, Self-Paced Course: Part II

0OUTLINE: The CHunks

Once the course overview has been defined, the organizing of content into manageable “chunks” is the next step. The best way to do this is to take your objectives and put them in an outline format. This “skeletal system” is an important component to building a successful course as it defines how the course will be broken down in a logical structure, giving order and flow to the information being presented. In addition, it helps the course stay on track with its purpose and outcomes, while allowing the course developer to identify excessive details that should be taken out in an effort to prevent cognitive overload (Meux, 1999).

Constructing an Outline

- Review the course objectives and identify the topic from each.

- Assemble the topics into the order in which they will be discussed.

- List subtopics under each topic.

- List additional points under subtopics, as needed.

Structuring course content in this way is like the method used in journalistic writing, known as the Inverted Pyramid. This method guides journalists to present crucial information at the beginning and taper down to the less important details. This is important in journalism for two reasons; the audience could stop reading at any given time, and when fitting articles into newspapers and magazines, the less important details can easily be cut without losing the story’s integrity. Similarly, the “additional points” in a course outline could sometimes be considered as less important details. It is up to the course developer to determine if these points align with the purpose and outcomes of the course, or if they are merely excessive details that can be discarded.

Resources:

Meux, C. (1999). How to write a course outline. Retrieved January 7, 2011, from http://www.ehow.com/how_2151340_write-course-outline.html

Structuring an Online, Self-Paced Course: Part I

5OVERVIEW: “Begin with the end in mind”

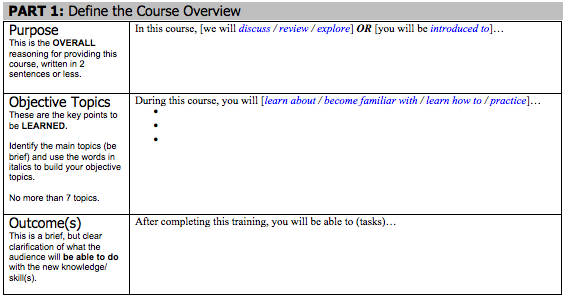

Be specific! Your introduction should clearly define exactly what your audience can expect from this course; it should not be a guessing game. If the audience does not know what to focus on, they are more likely to disregard important information unintentionally as our minds can only take in a certain amount of content at any given time; referred to as cognitive overload* (Bozarth, 2010). Never assume your audience knows your intention. Make your intention known! To help you do this, always define the following for each course you create:

- Purpose

- Objectives

- Outcomes

By mapping out the course overview from the beginning, you provide:

- yourself with a roadmap to keep the content focused,

- the audience with a clear picture of what they will be learning and come away with, and most importantly,

- a clearly structured course that will ensure success.

Identifying the PURPOSE

This is the “overall” reasoning for providing the course.

Identifying the OBJECTIVES

These are the key points to be learned. First, identify the main TOPICS (in one to two words only), then construct your objective sentences, informing the audience of what they will be doing, using key sentence starters (see chart below).

Identifying the OUTCOMES

This clarifies what the audience will be able to do with the new knowledge and/or skills.

As funny as it may sound, it is TRUE…”You can’t do without the P.O.O.!” ~Shanna Falgoust

Resources:

Bozarth, J. (2010, June 8). Nuts and bolts: find your 20%. Learning Solutions Magazine: Home. Retrieved December 16, 2010, from http://www.learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/472/nuts-and-bolts-find-your-20

Ezine. (2009, July 17). Tracy Schiffmann – EzineArticles.com Expert Author. Ezine Articles. Retrieved January 21, 2011, from http://ezinearticles.com/?expert=Tracy_Schiffmann

Schiffmann, T. (2009, December 22). Writing Curriculum For Adults – Begin With the End in Mind. Ezine Articles. Retrieved January 21, 2011, from http://ezinearticles.com/?Writing-Curriculum-For-Adults—Begin-With-the-End-in-Mind&id=3453916

Chunking Content

0The main challenge presented to a course designer is the limited capacity of the working mind to retain information at a given time. Therefore a strategy, referred to as chunking, breaks down information into bite-sized, manageable pieces of information the brain can easily identify and digest. Chunking is essential to online learning, especially self-paced courses, as there is not an instructor to answer questions and guide the learning process. This strategy groups together conceptually related information to help the learner form meaningful connections and promote comprehension (Malamad, 2009).

An additional benefit to grouping related information is that content duplication is typically eliminated in order to create a more clear, concise and efficient course! ~ Shanna Falgoust

Chunking Methods

- Have a Solid Internal Structure/Outline – Use chunking while determining the organization method for content.

- Start with large chunks of conceptually related content (Topic or Module level).

- Divide large chunks into smaller related chunks (Subtopic or Lesson level).

- Continue this process until content is broken down into its lowest level.

- As you become more familiar with the content, fine tune the internal structure.

- Chunk at the Screen Level – Organize the content so each screen consists of one chunk of related information. As a guiding rule, avoid introducing multiple topics, learning objectives or concepts at one time. If the chunk of content requires the learner to hold more than a few things in memory at one time in order to understand it, break it down again using visuals and text in multimedia to lessen demands on the working memory.

- Turn Bits into Chunks – Use any strategy that turns individual bits of information into meaningful chunks. Working memory can hold four chunks or four bits of information. By grouping small bits of information into one chunk, learners can process more at one time (Malamad, 2009).

Employ simple visual design basics; use white space and fonts as organizing tools, and make use of meaningful (not decorative) images that teach (Bozarth, 2010).

Resources:

Bozarth, J. (2010, August 3). Nuts and bolts: brain bandwidth – cognitive load theory and instructional design. Learning Solutions Magazine: Home. Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://www.learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/498/nuts-and-bolts-brain-bandwidth—cognitive-load-theory-and-instructional-design

Malamad, C. (2009, September 23). Chunking information. The eLearning Coach. Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://theelearningcoach.com/elearning_design/chunking-information/

Organizing Methods for Instructional Design

0- Alphabetical – As most people learn how to use alphabetical order in childhood, it’s nearly intuitive.

- Categorical – There is no hierarchy, no sequence and all topics are typically the same level of difficulty with no prerequisites.

- Cause and Effect – Used when content presents problems and solutions.

- Inherent Structure – For content presents events in a time line, or revolves around various geographical areas.

- Order of Importance – Learners pay the most attention to the beginning and end of a topic, therefore you can:

1) place the most important content at the start AND the end,

2) proceed from the least important to the most important content, or

3) go from most important to least. - Simple to Complex – Organized from simple to complex providing a slow initiation into a subject, building the learner’s confidence and knowledge base.

- Sequential – When presenting a process or procedure, it’s most effective to use a series of steps providing hooks for learners to remember.

- Spiral – Revisits each topic in a systematic way at a more detailed and complex level each time.

- Subordinate to Higher Level (Hierarchical) – Used when content requires learner master subordinate skills or knowledge to advance to a higher level skill.

- Whole to Parts – Introduces the big picture or system first, then delves into the parts of the system. Providing the big picture helps adult learners make sense of information. It also provides a framework for fitting information together in memory (Malamad, 2009).

Resources:

Malamad, C. (2009, November 30). How to organize content. The eLearning Coach. Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://theelearningcoach.com/elearning_design/how-to-organize-content/

Why Implement Instructional Design?

0- The organization of content provides a meaningful structure that is logical;

- Structure is imperative in helping end-users comprehend and retain content; and

- Structure within a course also helps end-users quickly find content they need (Malamad, 2010).

Defining the content structure is not often an easy task. Instructors or Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) develop face-to-face facilitated courses to flow based on their own preference and grouping structure. In these instances, fundamental details are often left out as the instructor typically presents main points and then merely elaborates on the details. An personalized grouping structure can hurt a self-paced course when it is converted from a facilitated course, as we all have different thought patterns, and it is never a best practice to assume an audience will automatically understand your thinking and intention. This is why it is imperative that instructors and SMEs review any face-to-face course needing to be converted to a stand-alone, self-paced course, and establish a basic outline, or visual structure, for the content. This will allow them to verify the course purpose and outcomes; and help them identify topics and subtopics that need to be covered, in order to establish the flow of the content. From this structure, the instructor or SME can then pull content from their current course and chunk the similar information together, supplying a more effective strategy for end-user cognition.

Resources:

Malamad, C. (2009, September 23). Chunking information. The eLearning Coach. Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://theelearningcoach.com/elearning_design/chunking-information/

Malamad, C. (2009, November 30). How to organize content. The eLearning Coach. Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://theelearningcoach.com/elearning_design/how-to-organize-content/

Game Development Curriculum Challenge

0As a middle school technology teacher, instructional designer, and game development in education advocate, I am curious to know WHAT TEACHERS NEED to either:

- get started in educational game development, or

- gain support with…

in order to further their or their students’ efficiency and success with this type of innovative curriculum. I am working with my sister, Anna Sexton, as she is a game development advocate at the high school level; and with my friend and mentor, Amanda Hefner, founder of the Texas Games Network and an officer of the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Special Interest Group, Games and Simulations (SIGGS).

If you are an educator or education administrator who has questions or concerns, or who is looking to further their understanding and knowledge in the area of game development in the classroom, respond to this blog. What do you need, what do your kids need, what ideas do you have, what successes or challenges have you had or are having, etc.? I will do my best to help you using my experience and any research I can find! If I can’t help, maybe another member will have insight they can share with our Gaming4Ed community to assist all of us in building a strong foundation for interactive game development as a successful learning strategy in our schools!

Literary Review: Motivating Secondary Students Through Game Play

81Walden University – Course 6653: Week 6 Application

Motivation is an emotional trait which provokes individuals to action or toward a desired goal, and offers purpose and direction to one’s behavior. Students are typically intrinsically motivated as this form of motivation is for pure self-gratification. Activities or experiences that challenge or stir their curiosity automatically inspire them to action. Understanding what motivates and engages students is a key factor when considering ways to promote learning in the classroom. Prensky (as cited in Hong, Cheng, Hwang, Lee, Chang, 2009) says it best in his statement, “a motivated learner cannot be stopped.” Today, educators have been tasked with integrating technology in the classroom in an effort to keep up with emerging technologies and meet the needs of these 21st century learners. One possible way to connect with today’s learners and integrate technology for learning is through the use of games. In this literary review, I have examined game play as a technology learning tool in the classroom and its motivational effects on secondary students.

Athanasis Karoulis (2007) conducted a qualitative case study through the observation of eleven students ages 6 to 14. In this study, Karoulis focused on the modality of a game (navigational structure such as help, next previous, home, etc.; and verbal or text-based narrative prompts) and their motivational factors on these students. The findings concluded that all of the pre-teen and teens, ages 12 to 14, were equally conscientious of all modalities and swiftly finished each scenario of the game. However, when the game did not provide new meaningful scenarios with increasing challenges, these students lost interest in the activity and stopped participating.

In contrast, Mansureh Kebritchi, Atsusi Hirumi, and Haiyan Bai (2010) collected information on sixteen empirical studies where games were used as a learning tool. Four of these studies were conducted on a secondary level and considered motivation as a dependent variable. From these four studies, two used a qualitative research method, one used a quantitative, and the final study used experimental and mixed methods. All four studies showed positive results in increased student motivation in the classroom; concluding this as a result of having a relationship between (or relevance to) the game and the students’ background knowledge. Both teachers and students reported that the math games, used as a learning tool, presented a slightly higher to very positive effect on class motivation.

In a more personalized study, Don Hernandez (2009) used mixed methods to research game play as a tool to motivate “at-risk” seventh and eighth grade students in his middle school to learn and build self-efficacy. In 2007, educational games were introduced to students during one of their math lab classes. They were taken through the game and given time to learn the modalities and objectives before the end of the lab, then students were given the option to join an after school gaming session. Due to increased interest, a morning session was opened as well. From the 2007-2008 to the 2008-2009 school years, the school’s math proficiency standards on the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) increased from 63% to 80% students passing at or above grade level.

In Herandez’s (2009) research, teachers who presented the math games in a lab, had prior knowledge of the game and how it operated, and therefore, took the time during the lab to ensure students understood how to properly operate the game, and gain the skills necessary to accurately engage in meeting objectives. In correlation, Beverly Ray and Gail A. Coulter (2010) emphasized the necessity in presenting, supporting and integrating the game as a class activity. Caftori (as cited in Ray and Coulter, 2010) indicated that educational games have minimal significance without the support of knowledgeable teachers. Scaffolding must be used to ensure that connections are being made between the game and the curriculum being presented to the students.

Hernandez (2009) and Ray and Coulter (2010) provide the most significant information in this research. Together, their research creates a clear picture, that when properly implemented and supported, educational games can have a strong motivational impact on students and their learning. Ten years ago, the US Senate reported (as cited in Paraskeva, Mysirlaki, and Papagianni, 2009) that the average seventh grader spent approximately four hours per week playing digital games. At that time, 77% played games at home (2000). Knowing that the majority of students today game or know someone who games at home for fun and for the entertainment value, integrating educational games properly in the classroom can create a powerful 21st century learning tool to enhance student motivation and engagement.

Through my research, I have found that not all educational games are useful in a classroom setting. True educational games must follow proper instructional methodology (pedagogy) and contain the principles of game-based learning (Hong, Cheng, Hwang, Lee and Chang, 2009), which defines what is being taught, the task objectives, who the learner is, and how the learned skill will be applied. In addition, games chosen for the classroom must contain a storyline or background that is familiar or relevant to students, and include age-appropriate scenarios and challenges that progressively increase as the player continues through the game. In addition, students need beginning teacher guidance on the game functions, have a clear understanding of the objectives, and be able to implement the skills necessary to achieving those objectives. Without these components, employing game play in the classroom will not demonstrate an increased advantage as a learning tool over traditional methods. Therefore, in continuing studies on game play as a motivational learning tool, researchers need to (1) identify the audience, (2) determine age-appropriateness of the educational game(s) that will be used, (3) identify the pedagogical design, (4) confirm game-based learning principles, (5) verify learning objectives, (6) establish a relationship or relevance to the student, and (7) confirm that the game contains variation with increasing challenges as the player progresses through the game.

In conclusion, it is obvious that there is need for new, more in-depth research that clearly takes into consideration the seven criteria identified above. Only addressing one or two of these criterions does not provide sufficient evidence into the use of educational games for the classroom, and subsequently skews the results or allows for misinterpretation of information. With the seven criteria in place, I do believe games can be an effective learning tool for the secondary classroom, and do believe games can motivate secondary students to learn. However, from the lack of evidence and formal research, my findings are inconclusive in regards to secondary students’ motivation to learn through the utilization of game play as a technology learning tool.

References

Ray, B., & Coulter, G. (2010). Perceptions of the value of digital mini-games: implications for middle school classrooms. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 26(3), 92-100. Retrieved from Education Research Complete database.

Hernandez, D. (2009), Gaming + autonomy = academic achievement. Principal Leadership, 10: 44-47.

Hong, J.-C., Cheng, C.-L., Hwang, M.-Y., Lee, C.-K. and Chang, H.-Y. (2009), Assessing the educational values of digital games. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25: 423–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00319.x

Karoulis, A. (2007), Educational games: motivation and the role of multimedia representations. South-East European Research Center, 315-321. Retrieved from http://www.seerc.org/ieeii2007/PDFs/p315-321.pdf.

Kebritchi, M., Hirumi, A., & Bai, H. (2010). The effects of modern mathematics computer games on mathematics achievement and class motivation. Computers & Education, 55(2), 427-443. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.007.

Paraskeva, F., Mysirlaki, S. and Papagianni, A. (2009). Multiplayer online games as educational tools: facing new challenges in learning. Computers & Education, 54(2010), 498-505.

Think Out Loud Evaluation: Computertan.com

0Walden University – Course 6712: Week 4 Application

References:

November, A. (2008). Web literacy for educators. Thousands Oaks: Corwin Press.

Reflection on My Learning Theory and Instructional Practices

5Walden University – Course 6711: Week 8 Reflection

At the beginning of the course, I mentioned that my personal learning theory included experience, meaningful patterns, emotion as a catalyst for learning, and memory. I develop beginning-of-the-year assignments that allow me to connect with my students by getting to know who they are and where they are coming from (experience). During this time, students learn about their classroom environment, procedures and expectations through habitual practices (meaningful patterns). In addition, I strive to provide a welcoming, non-threatening environment (emotion) where students can communicate and collaborate. Reflecting on my learning theory after going through this course, I do not believe I would change anything.

However, I do see a need to be more aware of my instructional practices. This course has taught me that there is a distinct difference between instructional technology tools and learning technology tools. Instructional tools are the tools teachers use to “show” students how to do something, while learning tools are tools that allow students to “engage” in activities to construct meaningful information. For instance, I often use a Smartboard in my classroom. I use this tool to SHOW students what to do. This is not as effective as having the students USE the tool to demonstrate concepts they are learning, or demonstrate understanding by using the tool to present information. Although I have always implemented both in my classroom, I now understand the difference and see the benefits emphasizing learning tools. With this knowledge I can adjust my instructional practices to better serve my students and enhance their learning.

Another technology tool I will use often to engage my students is a program called Inspiration; the Web 2.0 equivalent is My Webspiration. This tool helps students develop connections with difficult vocabulary and concepts. They are able to visually construct meaning by brainstorming what they might already know about the term or concept, and then build upon what they know to make new connections.

A couple of long-term goals for incorporating technology into my instructional practice is to continue to seek professional development where I can stay up-to-date on emerging technologies that interest our students, and form professional connections with other educators to have a sounding board to brainstorm instructional practices and ways to implement various technologies into the classroom as a learning tool. To do this I can research online educator communities and professional development opportunities in and around my area. I can join a forum or be a part of a group of educators who are exploring new ways to engage students in the classroom in order to help them be successful life-long learners.

Voicethread: Developing Self-Sufficient Learners

3Walden University – Course 6711: Week 5 Application

My Voicethread link: http://voicethread.com/share/1262122/